In Praise of the Book of Common Prayer

I've decided that I have been in need of a more disciplined life. Even though I surf, I don't really do much else in terms of exercise. Added to that, I've been in a kind of funk in regards to the priesthood—meaning that I have frequently found myself not as excited about the life of the priesthood as I otherwise have been. All “jobs” have their ups and downs and so I don't think this is something of which to be too concerned. At the same time, I have been seeking out ways in which to enliven my own sense of vocation.

Saitama of One Punch Man fame inspired me on the exercise front. I introduced my eldest son to the show while he was home sick recently and we both got really curious about the whole “100 push ups, 100 sit ups, 100 squats, 10 km run” daily regiment (if you've not seen the show, I dare not spoil anything and so I will offer no other context). While I was not about to go that extreme, I did give 50 squats a try and experienced probably my first ever exercise high. So I've taken on the discipline of doing 50 squats a day as an initial step toward better overall health.

When it comes to my spiritual exercise, I was reminded of the need to say the Daily Office. In the Church of England, clergy are required to say Morning and Evening Prayer every day. We Episcopalian clergy are not under the same requirements, probably to our detriment. When I was a rector and school chaplain, around half a decade ago, living on a school campus, I had a daily custom of sitting on a bench at the side of a pond and saying Morning Prayer with my prayer rope and a mug of coffee. These were spiritually rich experiences and I realized that I had neglected the habit, much to my detriment. So now I've begun getting back into the routine of saying Morning Prayer, straight from the Book of Common Prayer.

I'd argue that the Daily Office (that collection of services in the Prayer Book that mark the hours of the day: Morning Prayer, Noonday, Evening Prayer, and Compline) contains the most distinctly Anglican aspects of our religion. The Eucharist is absolutely presented in a particular, Anglican way. However, the nature of the Eucharist is truly “catholic” thus has moments that are common to many Christian traditions. The Daily Office, on the other hand, feels profoundly ours. At least it does for me.

The Office makes extensive use of the Psalms. It is frequently the case that appointed psalms are more lengthy than those of the Eucharistic services. For many years I had a distaste for the psalms, heartily agreeing with “God” as depicted in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

*“...and those miserable psalms...”

*“...and those miserable psalms...”

But I've really come around on the Psalms the more I read them. The language is rich and I can see how much of an impact they have had not only on the wider scriptures, but on the liturgical language of our Church as well. Also, given how often they speak critically of the wealthy and upliftingly of the marginalized, I've begun to wonder if there's any correlation between those who pray regularly with the Psalms and those who deeply oppose what is happening in the current regime occupying (and demolishing) the White House. But that's a discussing for another time, perhaps.

This is all to say that Morning Prayer has reminded me of the richness and beauty of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer and makes me lament a bit the direction in which we've gone—not only as Episcopalians, but as Anglicans globally. Because I can't help but notice that we Anglicans have, for the past fifty years, have been experiencing our most fracture-prone period of time in Anglican history and that this has coincided with a trend away from a Book of Common Prayer and more toward “common prayer” being an authorized library of resources. I also can't help but notice that such a shift is deeply “contra” to the Anglican ethos and has seemed to foster a chain reaction of trying to redefine anti-Anglican things as Anglican. And we happen to see this latter notion far more prominently from the “conservative” wing of global Anglicanism, those one would assume are more interested in being very Anglican.

***

A strange thing can happen in the Episcopal Church: one can live their lives in an Episcopal parish, even as a priest, and never engage with the Book of Common Prayer. There are so many authorized resources that one can make use of liturgies for every walk of life and never once put a hand on what we call the BCP. Now, a recent ruling of the General Convention of the Episcopal Church (the main legislative body of our denomination) has passed a first-read resolution to change our canons to say that, in effect, the term “Book of Common Prayer” is inclusive of all authorized liturgies as they currently stand. This was done largely to address a problem presented by same-sex marriage being authorized in the Episcopal Church (see note at the end). If this passes the second reading at the next General Convention, then the Book of Common Prayer ceases to be a book and instead becomes something far more nebulous. The problem with this, from my perspective, is that such a thing runs counter to maybe the most foundational aspect of Anglican Christianity, what I call “elegant simplicity.”

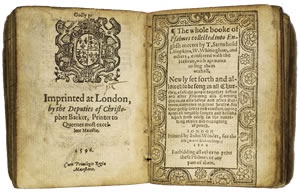

See, the Book of Common Prayer is maybe the most impactful document to come out of the Reformation-era aside from vernacular translations of the Bible. Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry VIII and Edward I (and martyred by Mary Tudor) did something truly remarkable. As I once heard Bishop Neil Alexander put it, Cranmer took a look at all the various books of the Church at the time and saw a key problem: there were different books for different people. The monks had their breviaries, the priests had sacramentaries, and the laity had some devotional books. What Cranmer did was take all the books around the Church, simplify them, consolidate them, translate them from Latin into English, and then gave them to everyone. So that both laity and clergy had the same book from which to draw—and this fostered a degree of transparency. The laity could now read for themselves what the priests and bishops were saying at the altar. But the central idea was that all Christians in the Church of England would be shaped by this particular resource, which in turn would also streamline and simplify the excesses of late-Medieval Western Christianity, giving us all—whether lay or ordained—a language of prayer that was “common.”

This helps further shape a key aspect of what it means to be Anglican: we are a people who believe most deeply in the practice and enactment of our beliefs. The Book of Common Prayer is, in effect, an explicit interpretation/application of scripture. Whereas, if you want to know what a Catholic believes you read the Catechism, or any number of Protestant beliefs are found in Confessions, knowing what an Anglican believes is found in worshiping with us. Our liturgies serve as our statements of belief. And this fact gets muddled the more we add options to the mix. Because this then fosters a divided Church, an Anglican Church with no sense of what is in “common.”

***

I want to be clear: this is not a screed against revision. Rather, it is a call against expedience and in favor of the difficult work of faithful revision. An Anglican Church without an actual bound volume known as the Book of Common Prayer is not an Anglican Church. It is instead a Church with a sort of vague “ethos” termed “Anglican.” In an increasingly dis-incarnating world rife with constant revision for revision's sake, a digital world, an analog approach is a form of faithful resistance. We Anglicans are deeply incarnational Christians, which necessitates a practice of intermittent liturgical revision. But such a practice is done to better enflesh the Gospel in the current generation, not to provide “preferences.” Preferences give ground to schism and apathy. Common prayer is a treasury from which we draw, holding us accountable to both each other and the Gospel that we have received.

Further, this is not a call for a single, universal Book of Common Prayer. A key part of our Anglican tradition is the revising of the Prayer Book in each autonomous province. Again, this is not in service of creating preferences, but in fostering what Anglican “common” prayer looks and sounds like in different cultural contexts. Episcopalians making use of the New Zealand Prayer Book is a problem because New Zealand's Prayer Book is for New Zealand's Anglican Christians. We can learn from that book and make use of things as part of our revision. But adopting it because we “prefer” the language of it is a tricky thing that, in my experience, teeters on the edge of cultural appropriation.

***

Matthew SC Oliver has written an excellent and raw letter to the conservative movement known as the Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON). A conservative himself, he argues that what GAFCON is ultimately espousing is something decidedly not Anglican. He notes that both GAFCON's view of the Bible and its understanding of the governance of the Church are innovative and not grounded in historical Anglicanism. I think he is absolutely right here, and I am not in theological agreement with much of what Father Oliver believes (though I highly admire his thinking and approach to how he believes what he believes—he's more of a “classical” Christian than a conservative, this latter term tending to be defined more by so-called “culture war” issues than any actual conserving). And this presents the fact that both “conservatives” and “liberals” in the Anglican Communion are guilty of the same things: moving beyond what defines us as Anglicans in order to achieve some particular goal, while trying to redefine “Anglicanism” to suit those purposes.

For me, this is the inevitable result of providing options and preferences rather than a commitment to common prayer. We are breaking up as a global communion of churches because we began breaking up on a local level. We abandoned common language, which then gave rise to an abandonment of common belief. As the well-worn saying goes “praying shapes believing.” Prayer that is uncommon shapes uncommon beliefs, thus undercutting what makes us Anglican on a fundamental level.

***

In his own preface to the Book of Common Prayer that he himself translated into ka ʻolelo Hawaiʻi (the language of the Hawaiian people), his late majesty King Kamehameha IV draws from Saint Paul's first letter to the church at Corinth, noting that a resource such as the Prayer Book is in service of what the Apostle teaches about orderliness. He writes:

In many places in the Word of God we are shown how established a thing it is that the Lord is to be worshipped in this way [referring to “common prayer” -ed.], that is to say, by offering our praise in one voice, by singing hymns in common, by saying prayers already prepared that all may pray in concert. At midnight, Paul and Silas prayed and sang Psalms unto God within the prison, and the prisoners heard them. (Acts xvi. 25.) And how should they have heard had those two not prayed together and in an audible voice? And how could their prayer have been otherwise than confused had it not been prepared beforehand and got by heart, so that their prayers and their praises were as one? This also coincides with what the Apostle Paul taught the Corinthians in more places than a few in his Epistles to them. The fourteenth chapter of his first Epistle to that people is full of his teachings on this particular subject and of the way in which worship ought to be offered, and how he was astounded at the multiplicity of their prayers and confusion of their worship: “How is it then, brethren? when ye come together, every one of you hath a Psalm, hath a doctrine, hath a tongue, hath a revelation, hath an interpretation. Let all things be done unto edifying.” Furthermore at the end of the chapter he gives this particular injunction: “Let all things be done decently and in order.” Not only are praises and thanksgivings to God to be dutifully prepared beforehand, but prayers also.

He continues later:

We are commanded to join in public worship, and should we meet, each one of us to choose his own particular prayer, or some to sing Psalms, some to declare a doctrine, and some to prophesy, we should be very like those Corinthians satirized by Saint Paul.

His majesty is writing to commend this form of worship over and against the Congregationalists in Hawai'i, who were the first to establish churches in the Kingdom of Hawai'i and who his majesty held deep distrust (since they also held significant economic control). He saw how each congregation worshiped in their own ways (hence the name). He recognized that aforementioned axiom: “praying shapes believing.” He wanted a Church for his people that would give them their own common prayer, knowing that such a thing is of crucial importance. In his own words, imagining a worshipper at a church that holds no common prayer (emphasis mine):

Alas for this would-be supplicant who could not pray to God, because he did not know what turn the prayer would take! because his heart was not as the minister's heart, and his needs were not those which the man put up to pray expressed; because no use was made of prayers prepared beforehand by those who knew of old the common wants of man — of prayers bequeathed to us by those we rightly call the Fathers of the Church; and because prayers which satisfy every mind and find at every repetition a new birth in every heart were unemployed. The prayers having been prepared of old, the Psalms ordered, the hymns sanctioned, the rites and offices authoritatively established, then, indeed, we can worship with all our mind, and all our heart, and all our strength; none can get up and offer crude supplications for things of no common interest; but on the contrary, we go to church knowing what the prayers will be and that they will convey to Heaven all our desires, yet nothing more.

Later,

The Church has not left us to go by one step from darkness into the awful presence and brightness of God, but it has prepared for our use prayers to meet the necessities of every soul, whether they be used in public or in private.

Such is the general character of this Book of Common Prayer now offered to the people of Hawaii.

Again, uncommon prayer shapes uncommon belief. It abandons the sort of common life that the gospel calls us to live. Common prayer is a gift to be received, put to use, to shape us and hold us accountable even as we engage in the work of faithful revision. Common prayer is deeply Anglican. Preferential prayer is not.

In other words, say your prayers.

***

Note: The BCP's rubrics, the little italicized notes found throughout the book, are canonically binding statements and are meant to reflect the “official” teaching of the Church. The rubrics of the Marriage liturgy denote that marriage is reserved for a man and a woman. Changing that language is complicated and would require multiple meetings of General Convention. However, the resolution that recognized the blessing of same-sex marriages was accompanied by an alternative marriage liturgy. And so, in order to address the issue in a more timely manner (and all in the midst of a process toward an entirely new Book of Common Prayer) it was suggested that we broaden the definition of what the BCP is, rather than wrangle over a single page of the book. At least that's my understanding of this.

***

The Rev. Charles Browning II is the rector of Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church in Honolulu, Hawai’i. He is a husband, father, surfer, and frequent over-thinker. Follow him on Mastodon and Pixelfed.