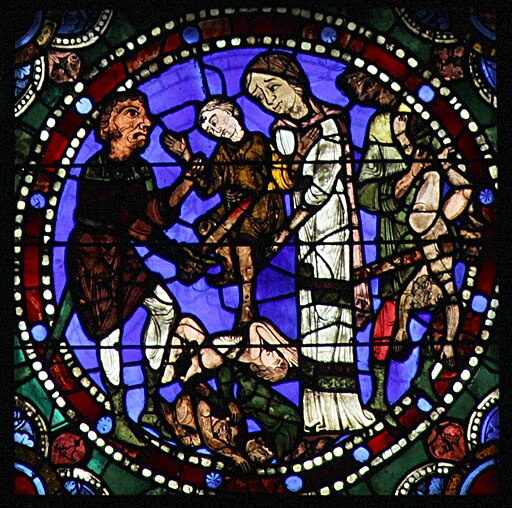

In my recent series on the commemorations for the week between Christmas Day and the Feast of the Holy Name, I managed to generate some small degree of controversy and discussion when I mentioned that the Massacre of the Innocents as recorded in Matthew’s gospel likely did not actually happen. As I said in that piece, there is no extra-biblical historical evidence that the event occurred. Even one of the most important historians we rely on, Josephus, did not include any mention of Herod killing scores of infants—and Josephus does not hold back on his criticisms of the Herodians.

Now, I am willing to admit one caveat, and that is there’s a theory that maybe the massacre happened, but it wasn’t a large-scale event involving thousands of children. Given the limitations of the information supplied by Magi, how many kids could have been born in the narrow window of a) when the star appeared and, b) in Bethlehem? If this was the case, then Herod ordering the murder of a small number of kids would hardly register among all the horrible things he was known for and might not garner a mention from historians and scribes of the time.

However, I still hold to the contention that Matthew is not interested in recording precise, “accurate” (as we understand the term) history so much so as writing a story that he feels is true in regards to Jesus. Perhaps the causes that lead to the Holy Family taking flight to Egypt were more of a slow-burn situation, where young kids were likely to die and so, inspired by God, Joseph takes Jesus and Mary (in an event that echoes also another Joseph—one who managed to shelter the patriarchs in Egypt during a time of famine). Matthew wants to express the dire situation to the Church and so telling a story about Herod murdering kids communicates that truth. It’s a story that feels true to who Herod is and is a kind of short-hand way of helping Christians born years, even decades, after the event understand what a monster the man was.

But this all serves as a way to address an important elephant when it comes to reading the Bible: it isn’t always historically accurate. This provides grounds for a kind of crisis of faith when we treat the whole “divine inspiration” thing in terms of what we call today “biblical inerrancy.” In other words, if the Bible is a book that God basically dictated to various writers and is, therefore, God’s actual words on paper, then what are we to make of things when the Bible and facts don’t line up? Is God lying to us? Does God get His facts mixed up? Or is there some demonic plot being enacted by historians and scholars to try and discredit the Bible? (This latter thing was basically the view of my church growing up; if the Bible and facts didn’t agree, then it was facts that needed to change—we can see such thinking happening in certain political circles today, but I digress).

In order to discuss this, we’ll need to break a few things down—namely, what we mean by “history” and what is meant by “divine inspiration.”

WHAT IS HISTORY?

History seems like a straightforward thing. It is the discipline of chronicling past events so that we can keep posterity and revisit what has come before, right? Yes. But our modern conception of history is something a bit different from what our ancestors thought of when they conceived of history. See, our current understanding of history is shaped by the scientific method, which came about in the 1700s. Prior to this, the phenomena of our world were seen in terms of analogy. Take, for instance, reproduction. We continue to use vestigial language from our agrarian past to speak of how organisms reproduce, language like “seed” and “fertility.” The word sperm comes from the Greek sperma which means “seed.” So, for much of human history, we saw all forms of reproduction as analogous to agriculture: a seed is planted in a fertile space where new life emerges. It wasn’t until the invention of the microscope and the advent of the scientific method that we began to challenge this analogy and see if there’s something else going on. What emerged during this time was the concept of facts.

Prior to the mid-16th century, the Latin term factum referred simply to “a thing done or performed.” This usage is still common in the legal realm. Those of us who grew up with Dragnet recall Joe Friday regularly saying to witnesses, “just the facts.” In other words, recall the events without commentary or elucidation. Deborah went to the store at 5:15 in the evening. But, with the emergence of modern science, facts began to take on greater precedence. Facts were considered pure and superior, a distillation of the essence of a thing. Facts represent something that is observable and repeatable. Deborah can go to the store at 5:15 and so can I. What I can’t do is inhabit Deborah’s frame of mind. I can’t know what she was thinking as she walked to the store, how happy or unhappy she might have been. The fleeting thoughts and emotions she felt during that stroll. These are all unique to her, making them not reproducible and, therefore, useless in terms of data. They are extraneous, important to Deborah perhaps, but not important for finding out if Deborah saw James fleeing the scene of Jesse’s murder, which happened across from the store at around 5:25.

Thomas Jefferson famously applied such thinking to the Gospels. Since miracles and other supernatural events are not reproducible, repeating and measurable phenomena, Jefferson stripped the gospels of any reference to them. Jefferson believed this made for a more “true” Gospel because it was a gospel of facts. The bias of the scientific method is that facts are truth. If something is not factual then it isn’t true. And something is only factual if it is an observable, repeatable event free from extraneous conditions. Deborah can go to the store at 5:15 regardless of whether she’s happy or sad or praying or thinking about the baseball game. Those things are ancillary to facts. What is personal to her is not, objectively, true according to modern science.

So when we record history, we now aim to be as factual as possible. I used to be a journalist and journalism is a key resource for historians. The discipline of journalism is to write things as dispassionately as possible, removing your own feelings and commentary and presenting things as “factually” as one can, leaving the reader to decide how to think and feel about those things.

Now, I’m not here to argue against facts. Facts are important. I’m simply attempting to demonstrate that, one, the prioritizing of facts is a relatively recent event in human history and, two, perhaps to suggest that facts leave a lot of things out of a story.

When I was a journalist I was also a creative writer, working on a novel, and getting short fiction and poems published in TINY journals and publications (I did manage to get once piece of fairly unhinged “fan mail” for a five-line poem that was picked up by a publication that was simply photo copied sheets of paper to be stuck onto bulletin boards and whatnot). Creative writing gives texture to facts. That’s where we dwell on Deborah’s frustration that the short-stop dropped the ball in the bottom of the ninth, causing the other team to get two runners to home plate, costing her team the game—and that this frustration mirrors the frustration she feels that her husband is always working too late to go to the store and grab a gallon milk for the house, leaving her to have to do it and making her feel like the center-fielder who had to make up for the short-stop’s mistake. Indeed, the creative writer will say that the real story is found in spots like these and not the facts. Facts make for poor story-telling.

The ancients knew this. When they wrote histories, they weren’t simply recording dispassionate facts. They were telling stories, stories full of texture and meaning. Their goal was to get readers to feel the story being told. In order to do this, elements might be told out of order, or hyperbole was employed, or even, at times, what we call “fiction” was used. The facts of the story might not be straight, but the Truth absolutely was.

Here’s an example from the gospels: Jesus’ cleansing of the temple. In the Synoptics (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) it serves as a kind of crescendo to Jesus’ story. The Synoptics all depict Jesus moving from Galilee and making His way to Jerusalem to where He enters in triumph, chases out the money-changers from the temple, which makes Him a more serious target of the religious authorities. But in John, Jesus cleanses the temple right at the beginning of His ministry, right after coming out of the desert and His 40-day-long bout with Satan. Further, John depicts Jesus going to and from Jerusalem on a regular basis. If all four gospels are true, how do we reconcile their conflicting facts? Do we say, as some have, that Jesus must have cleansed the temple twice? If that’s the case, why don’t all four gospels testify to that?

Perhaps we’re thinking of this incorrectly. We need to get back to that ancient way of thinking and consider that Truth is something that cannot be reduced down to simple facts. As Ian Markham, the dean and president of Virginia Theological Seminary, is know to say, we Christians do not read a book, we read a life; the book is important because the book testifies to the life. Given this, no true story of a life can be told only in fact. Truth moves beyond fact. And so, as a result, it doesn’t really matter when Jesus cleansed the temple. What matters is that Jesus is someone who cleanses the temple, whether as the culmination of His earthly ministry or resulting from being in the power of the Spirit after overcoming the devil in the wilderness. The facts of the story are in service to the Truth.

WHAT IS DIVINE INSPIRATION?

There are, of course, many many misunderstood passages in the Bible. Many of them are found in the writings of Saint Paul. This shouldn’t surprise us because even the Bible itself tells us that Paul is hard to understand, with Saint Peter writing:

Consider the patience of our Lord to be salvation, just as our dear friend and brother Paul wrote to you according to the wisdom given to him, speaking of these things in all his letters. Some of his remarks are hard to understand, and people who are ignorant and whose faith is weak twist them to their own destruction, just as they do the other scriptures. (2 Peter 3:15-16 CEB)

This is an important passage for a couple of reasons. First, it shows that the Church received Paul’s writings as scripture fairly early on. Second, it gives us a fun little insight into the lives of the early saints: even one of Paul’s friends—the one considered to be the first pope—has a hard time understanding what the heck he’s saying.

But one of the most broadly (and, I’d argue, dangerously) misunderstood things Paul wrote comes from a letter he wrote to his young protege named Timothy:

All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness: (2 Timothy 3:16 KJV)

And let’s also use the NIV version, since that’s arguably the one most people would know these days:

All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, (2 Timothy 3:16 NIV)

So, here Saint Paul teaches that “all scripture” is “inspired,” which is translated as “God-breathed” in newer English versions. This leads us to the conclusion that “scripture” is something breathed from God, thus God’s very words, transcribed by holy writers. Or is it?

Before we begin to look at what it means that something is “God-breathed,” we need to take a look at the word “scripture.” We use the word exclusively for religious writings, but in its original sense “scripture” simply means “a thing written.” So, “writings.”

To put the passage literally, it would read “All writings are God-breathed.” Is this what Saint Paul is saying? That all writing is breathed out by God? Not only the Bible, but the Qur’an, the Upanishads, the Book of Mormon? Not only “religious” books but also The Catcher in the Rye, the Godzilla collectibles guide on my shelf, and the instruction manual to my TV? I don’t think this is what Saint Paul is teaching Saint Timothy.

The word “scripture” (graphe in Greek) is used exclusively in the Bible to refer to the writings of the Bible. We saw this a bit earlier with Saint Peter using the term to refer to Saint Paul’s letters. Elsewhere, it is used in reference to the books of the Old Testament. So the term seems to be applied to certain writings in this context.

Now, a lot of Christians will say that in this case “the scriptures” is simply short-hand for “the Bible.” But things are not that simple. For one, there was no such thing as “the Bible” when Paul was writing Timothy this letter. You might say “well, okay, sure; the New Testament wasn’t all written yet, but there was the Old Testament.”

It may surprise you to learn that what we think of as the Old Testament did not exist until around the 600s at the earliest. That’s 600 AD (or CE nowadays). As in, 600 years after the time of Jesus.

Now before you start writing me emails or replies on Mastodon, let me finish. I’m not saying that the writings themselves didn’t exist until then. I’m saying that the writings that make up the Old Testament as we know it were not put together into a definitive collection of 39 books (24 in rabbinic Judaism because a few of the books are consolidated and treated as a single book, notably the minor prophets) until that time. Yes there were translations of these books into Greek (called the Septuagint) and for many Christians those translations were treated as “the Bible” of their time, but given that some of the books are never referenced in the New Testament and they did not exist in a single volume, there is some question over what books were considered “official” back then. The group of rabbis known as the Masoretes were the ones who assembled the Old Testament as we know it in the 600-900s. Their list of books is what is used by Protestant Christians for the Old Testament.

This is all to say that the term “scripture” was something coming into form at the time of Saint Paul’s writing. And his use of the phrase “God-breathed” is likely a mechanism to help Saint Timothy know what writings are truly Christian and which ones to avoid. This is especially crucial given the preponderance of gnostic and anti-Gentile writings making the rounds at the time.

Perhaps seeing the passage in some wider context will help us. I am fan of the Common English Bible, so I tend to use that:

But you must continue with the things you have learned and found convincing. You know who taught you. Since childhood you have known the holy scriptures that help you to be wise in a way that leads to salvation through faith that is in Christ Jesus. Every scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for showing mistakes, for correcting, and for training character, so that the person who belongs to God can be equipped to do everything that is good. (2 Timothy 3:14-18 CEB)

It might be bad scholarship on my part, but I tend to read the passage like this: “Every scripture that is inspired by God is useful for teaching,” etc. In other words, Saint Paul is reminding Saint Timothy that he is able to discern which writings are “God-breathed” and which ones aren’t. This isn’t so much a working definition on the doctrine of scripture as much as it is a piece of practical wisdom: if it doesn’t sound like scripture, then it isn’t. It’s one of the reasons that we can say that something like the Gospel of Thomas doesn’t bear the aroma of God’s breath—it ends with Jesus telling Saint Peter that Saint Mary of Magdala will need to be reincarnated as a man in order to enter heaven. And those “God-breathed” writings serve the purpose of instruction and formation to make for good Christians.

So the Bible itself does not define itself as being the result of God dictating His words into the ears of particular people. Rather, God breathes through the words that have been written, giving those of us who know Him through prayer and devotion the means to recognize Him in particular writings. Those writings are valuable because they evoke the very breath of God—like us!—and therefore have something to say about the sort of people God wants us to be.

TRUTH IN FICTION

This brings us back to the question of fiction and the Bible. Can the Bible contain fictional material and yet remain true? Yes.

Let’s ask this question a slightly different way: can God’s breath be detected through fiction? If we say no then we risk limiting God… Given that God is sovereign and gets what He wants because He is God, it is very much the case that God can use fiction as means for declaring His truth. Indeed, the book of Job is pretty much accepted as being an intentional work of fiction, but is held dearly as a source of beauty and truth—especially for those broken-hearted and desperate for God. Aside from that, we have entire books of poetry in the Bible and poetry is a medium that is not tied to mere fact, given to expansive and hyperbolic language in order to express Truth, God’s Truth.

So, the Bible isn’t always factual. That’s okay. That doesn’t mean it isn’t true. God can use fiction to express His Truth to us. Fact or fiction doesn’t matter as much as whether or not we can detect the presence of God’s breath in the story, whether or not the story is useful for teaching us and forming us into the sort of humans He has redeemed us to become.

***

The Rev. Charles Browning II is the rector of Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church in Honolulu, Hawai’i. He is a husband, father, surfer, and frequent over-thinker. Follow him on Mastodon and Pixelfed.

*“...and those miserable psalms...”

*“...and those miserable psalms...”