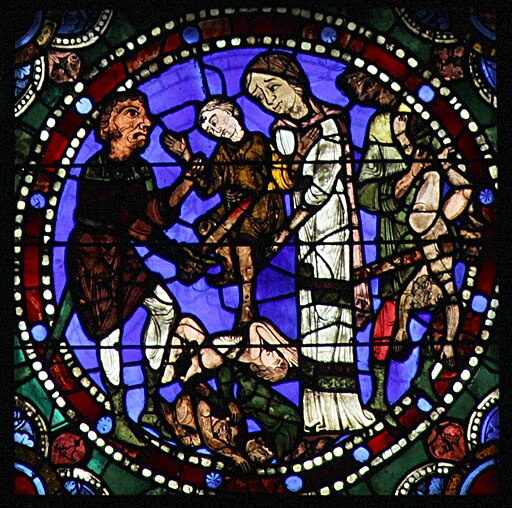

On the Holy Innocents

I was first really exposed to the Christian commemorations of the Holy Innocents thanks to a church name. Holy Innocents Episcopal Church outside Atlanta, to be exact. I visited that church and liked the architecture and liturgy and it inspired me to learn more about a story I had known since childhood but seldom dwelt on—much less saw as a focus of devotion.

It’s a story that largely gets left out of our Christmas commemorations in the Episcopal Church, partly because it is such a horrible story (and likely partly due to the more modern doubt of the story’s historical accuracy, which we’ll talk about in a bit). No one wants to follow up Christmas morning with a service about the mass-murdering of children.

At the same time, especially this year, this is a highly relevant story. Tragically, all over the world, politicians are playing like Herod and systematically executing anyone they deem a threat—including children.

Holy Innocents, also known Childermas, commemorates an event that, in all likelihood, never happened. Josephus, an important Jewish historian, took great care to showcase the brutalities of the Herodians and never once mentioned a mass slaughter of children. Outside of the gospel of Matthew there are no other historical accounts of this story and it seems likely to be something meant by the evangelist as a means to make connections between Jesus and Moses, a common theme throughout that particular gospel. So what are we to make of this fact? That we not only have a day marked on our calendar but also name churches and schools for an event that probably never happened?

This is one of the tough parts of reading the Bible. It’s not always “factual” in the ways to which we are accustomed today. Nevertheless, elements that we deem “fictional” can have a huge impact on our faith and wind up speaking Truth despite their (in)accuracy.

Consider the typical Christmas pageant. Aside from Mary, Joseph, a baby, angels, and some shepherds most of the story we dramatize is completely fictional and not related to what is written in the Bible. We tend to think of the birth of Jesus as being an event that culminates after Mary and Joseph, alone on a donkey, have gone to every house or inn in Bethlehem and been told “no vacancy” and so set up shop in a nearby stable. But none of the gospels mention a donkey and we’re only told that there was no room in “the inn”—nothing at all about conversations with inn-keepers or a door-to-door journey. Further, given the nature of the census, there was probably a caravan of people traveling to Bethlehem and others taking residence among the livestock because Bethlehem was not prepared for such an influx of extra people. What we think of when we think of the Christmas story is largely fictional, but that doesn’t mean there’s not truth in those elements. We crafted those details over the centuries in order to “flesh out” the story a bit, to give it the sort of texture that it invites. And those added details speak much of the faith and mindset of the church that crafted them.

The same is true of the Massacre of the Innocents. It might not have happened, but it’s very telling that no one finds the story improbable. There might not be any records to back it up, but the story sounds like the sort of thing Herod would have done—indeed, the sort of thing that rulers all over the world and all over our history books have done.

The sort of government that gleefully cancels aid and assistance to poor countries is acting like Herod. The one that uses starvation, particularly of children, as a weapon of retaliation is acting like Herod. The political entities that travel throughout villages to murder women and children are the ones acting like Herod.

The actual Herod may not have ordered a campaign to murder the children of Bethlehem out of some fear of losing power, but Herod for sure murdered plenty of children and other innocents during his reign out of a sense that because he was in charge he could do so—without any fear of God. And in this, Herod is an archetype. Plenty of gilded so-called rulers kill innocents in the name of preserving their name on the side of buildings. If they were honest, they do so out of a desire to kill the God that they are not.

Yesterday’s saint records Jesus saying “If the world hates you, know that it hated me first.” The poet Dianne di Prima says in her poem, “Rant” that “the only war that matters is the war against the imagination, all other wars are subsumed by it.” I tend to think that it’s more the case that all hatred is subsumed in hatred for Jesus and, therefore, all wars are the Battle of Armageddon, the war against Christ Himself.

If the story behind Holy Innocents is fictional, then it is worth asking what it is we’re commemorating this day. I think the answer is simple: Holy Innocents commemorates all children sacrificed on the altar of expedience or inconvenience by those in power attempting to cast themselves as gods. Those killed by starvation from the abrupt end to programs like USAID or in Gaza by the Israeli government. Those killed by radicals in Somalia and Sudan. Those dying thanks to bombs dropped on Ukraine. And that’s only looking at what’s currently happened in the news in recent weeks. These are who we commemorate on Holy Innocents. The gospel story is subsumed in the stories we see right now, and is itself reflective of those stories. The gospel story helps us Christians see the shape of the story happening around us, helps us in remembering where our allegiance lies.

Herod is the one who oversees the death of innocents. Christ is the one who sees them as holy.

***

The Rev. Charles Browning II is the rector of Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church in Honolulu, Hawai’i. He is a husband, father, surfer, and frequent over-thinker. Follow him on Mastodon and Pixelfed.

#Christmas #HolyInnocents #History #Theology #Church #Christianity #War #Gaza #Ukraine