On Saint Thomas of Canterbury

I’m sorry to say that I was not very familiar with Saint Thomas Becket (also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury) until recently. He’s quite an important English saint with a famous memorial altar in Canterbury Cathedral that marks the spot of his martyrdom (seen in the header image). His shrine is also the place to which the characters in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales are traveling and sharing their stories. The liturgist Richard Giles feels that Saint Thomas should be the patron saint of England.

Thomas Becket (sometimes “Thomas a Becket”) was the archbishop of Canterbury in the late 1100s. He was the son of a Norman family and managed, with great ambition, to become a highly valued member of Henry II’s inner court. The king saw an opportunity when Archbishop Theobald Bec died. Henry figured he could appoint a kind of ringer in the senior office of the Church in England, and so he managed to get Thomas appointed—despite the fact that Thomas was not ordained to any clerical office at the time. Within days, Thomas was ordained deacon, priest, then bishop in order to take charge of the archbishopric. He came to this office in the midst of a time when the English monarchy was attempting to both exert further control over the church and gain further independence from Rome. But Thomas had a fairly dramatic conversion experience as a result of his impromptu ordinations and wound up eschewing the vainglory of the royal court in favor of faithfulness to the Church. Once Henry’s close friend, he became a thorn in the side of the king and was regularly opposing him on church-related issues, even threatening excommunication at one point.

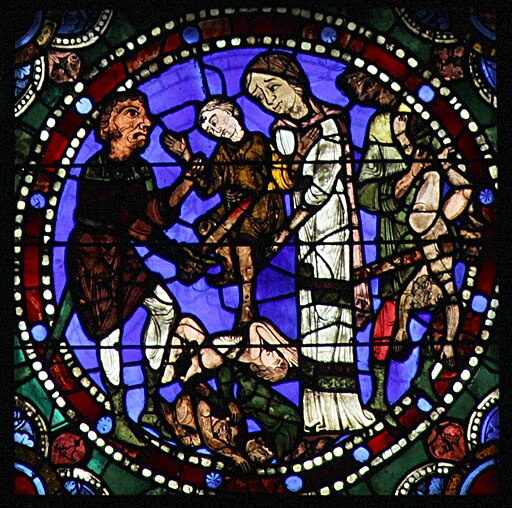

The story goes that Henry II, in a fit of frustration (and after Becket had been allowed to return from a multi-year exile in France), exclaimed among some of his advisors and knights “will no one rid me of this troublesome priest” (or some variation of this). Four of his knights took this as an order and made plans to assassinate Saint Thomas in the Cathedral. He was stabbed multiple times while Vespers was being chanted, the events expressed in gory detail by one of the monks wounded in the attack.

There are complicated elements in Saint Thomas’ story that carry overtones we still deal with today. Becket wanted “secular” legal systems to have limited authority over the clergy, preferring that the Church handle its own affairs. Such a practice has come to a head in the early 21st century where we’ve seen that when the Church is left to its own devices in terms of addressing clerical crimes, justice becomes elusive. However, at the same time, we also see the dangers inherent in a system where a government exerts control and influence over the Church. Becket was a champion of the established models of medieval Christendom, where monarchs were understood to be under the authority of the Church, with bishops serving as a kind check on kingly power. Henry II did not want to be held in such check and his frustrations with this idea ultimately led to the death of a beloved archbishop.

Thomas’ assassination is of a piece with other notable Christian leaders who attempted to challenge worldly power with the power of the gospel. Oscar Romero is one example, assassinated during Mass by right-wing political figures. Martin Luther King Jr. is, of course, another—assassinated because he became a more vocal opponent of the war in Vietnam and was beginning to shift his advocacy toward the exploitation of the working poor. Both saw their stances as being rooted in the gospel.

Thomas is a worthy saint for our consideration and devotion in our time. There is much pressure put on the Church (in all her forms) to capitulate to worldly powers. The radical right movements like MAGA and their ilk are the most current (and perhaps most egregious), but I’ve seen such pressure come from the left-side of things as well. Having grown up in a church quite given to right-wing political and social evils, I’m loathe to see a similar thing happen with more “progressive” churches like the Episcopal Church, where subscription to partisan talking points becomes seen as synonymous with “the gospel.” Indeed, I am of the conviction that faithfulness to Jesus Christ and His gospel will result in frustration from all forms of political partisanship. Jesus is one who disturbs worldly power, not one who makes it feel comfortable. If the Venn Diagram of one’s partisan politics and their theology is a circle, there’s a problem.

It is said that Thomas was prayerful and pious even as he was being struck by the swords. When the knights entered the cathedral, the monks wanted to bolt themselves in the sacristy for safety but Thomas would not let them. “It is not right to make a house of prayer into a fortress,” he said. After the third blow with a sword, one of the survivors of the attack recalled Becket as saying: “For the name of Jesus and the protection of the church, I am ready to embrace death.”

Saint Thomas of Canterbury was willing to face death rather than capitulate; choosing the assassin’s blade over easy comforts provided by temporal power. When his body was removed from the nave of the cathedral and his episcopal vestments removed, his fellow monks discovered that Thomas wore a hair shirt underneath it all—a garment of great discomfort and used for spiritual discipline and penance. It was a sign of the deep devotion this man had. Do I have the same level of devotion? Do you? How willing are we to hold to the gospel that’s been handed down to us in the face of pressure, coercion, even death? This is a challenging question.

Faithfulness is not always easy. Saint Thomas, like Saint John and Saint Stephen before him, testifies to this fact. The powers of this world are more than ready to execute anyone in service of their claims to power—the testimony of which Saint Thomas shares with the Holy Innocents.

Again, the Christmas season is not all garlands, tinsel, gifts, and lights. It is also blood and travail. This dichotomy is quite strikingly expressed in the hauntingly gorgeous Christmas hymn “A stable lamp is lighted.” I have us sing this hymn every Christmas Eve as a reminder that Christmas leads us to Easter, but we have Good Friday as an unavoidable stop along the way. The first verse of the hymn is a beautiful exposition on the Nativity story:

A stable lamp is lighted whose glow shall wake the sky; the stars shall bend their voices, and every stone shall cry. And every stone shall cry, and straw like gold shall shine; a barn shall harbour heaven, a stall become a shrine.

But the third verse takes us to Calvary:

Yet he shall be forsaken, and yielded up to die; the sky shall groan and darken, and every stone shall cry. And every stone shall cry for gifts of love abused; God's blood upon the spearhead, God's blood again refused.

The saints of the first week of Christmas embody this tragic element. The babe in the manger will ultimately, despite His dedicated following and popularity, be rejected because He usurps the status quo, overturns the way-things-are. Certain people will “come and adore Him” only to a point. So long as He stays in that manger, things are fine. It’s only when He grows and enters a house of prayer to drive out corruption that certain people begin to reconsider their love and commitment of Him.

The final verse of “A stable lamp is lighted” offers us a powerful closing word:

But now, as at the ending, the low is lifted high; the stars shall bend their voices, and every stone shall cry. And every stone shall cry in praises of the child by whose descent among us the worlds are reconciled.

In the end, as Saint John testified, the way-things-are will ultimately fall away to a world made as new. The sorts of powers that kill innocents and saints will be unmade and the world will be set as it was made to be.

***

The Rev. Charles Browning II is the rector of Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church in Honolulu, Hawai’i. He is a husband, father, surfer, and frequent over-thinker. Follow him on Mastodon and Pixelfed.

#Church #England #Episcopal #Anglican #Christian #Theology #History