Ten years ago today, the Obergefell decision was handed down, making civil marriage legally available to same-sex couples nationwide. It just so happened that this decision arrived within a day or two of the General Convention of the Episcopal Church taking a vote on redefining the marriage canon of the church to include same-sex marriages. In addition, the appointed scripture readings for that Sunday included the story of David and Jonathan, a story about deep love between two men that has long been embraced by gay Christians. For me, these three things coinciding felt like a divine occurrence.

At the time, I was the rector at The Chapel of Saint Andrew in Boca Raton. The congregation was fairly politically diverse and so it felt right and proper to have a series of discussions on the changes that were happening in society and the Church. Those discussions prompted me to write a five-part series on the blog of The Chapel (now lost to ether of the internet…). I’ve long maintained that one can be a “traditionalist” Christian while also being open to things like same-sex marriage in the Church. So I saw these discussions as a catalyst for articulating a Biblical and theological (and ecclesiological) view of Christian marriage that is in continuity with the tradition but recognizes that God might be leading us to do “new things” as so often is the case in the scriptural tradition.

On this tenth anniversary of the decision, in the year 2025, renewed attacks on same-sex marriage have arisen. The Obergefell decision seems less secure. The Southern Baptists have reiterated their opposition to same-sex marriage, following a wider “spirit” of Christian hostility to the idea. And so, it seems appropriate to republish some of my series here. Others, back in 2015, found it helpful and so I hope you might as well.

What follows are the first two parts of my series: how we Episcopalians read the Bible and what the Bible itself actually says about same-sex marriage. I also include material from the last post of the series, made up of my own personal reflections. Keep in mind that these are being represented as they were written in 2015. My writing has probably improved in that time and some of my theology may have changed. Please be gracious.

—Fr. Charles+

THE BIBLE AND EPISCOPALIANS

In discussing same-sex marriage in/for The Church one is obligated to be aware of “what the Bible says.” The Bible (and a particular reading of it) dominates the conversation.

It is true that so-called “progressive” Episcopalians are put at something of a disadvantage on this topic because, as the so-called “conservative” Christians will quickly assert, the Bible is clear that homosexuality is a sin in the eyes of God. This is, for many, something that is non-negotiable.

One can point to the Bible and say “here’s what it says.”

I’m reminded of a former class-mate of mine in college who was an Evangelical Christian. She and I got into a discussion about the Bible and I made mention of “gray areas.”

“There are no gray areas in the Bible,” she stated without hesitation. “The Bible is black and white. There are only those parts of it that you disagree with that you want to interpret away.”

Her words are pretty consistent with what many of us hear in this conversation.

Before we get into the discussion of the Bible itself, I think it is important to talk first about how we read the Bible.

We are Anglican Christians. This means that we have a distinct way of being Christian. The past several decades have seen a shift away from denominational distinctiveness in favor of a loose commonality in an attempt at Christian unity. The result, however, has largely been to allow Evangelical Protestantism to dominate all non-Catholic ecclesiologies. This is a troubling trend.

Evangelical Protestantism tends to understand the Bible as a book that is to be taken literally, at face-value, a book containing everything we need to know about life. This is expressed in a bumper-sticker I’ve seen more than a few times: The B.I.B.L.E.—Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth.

A point that many Christians are quick to forget or not notice in the first place is that the Church has never had a universally recognized doctrine in regards to the Bible. Indeed, most (if not all) “doctrines” on the Bible are products of the late Protestant Reformation-era (at the earliest).

Martin Luther, the German Reformer, gave us the popularly known term “sola scriptura” which means “scripture alone.” It was this notion that created the context for a key component in Protestant Christianity: the Bible is the final and ultimate source of authority for the Church.

Following Luther, John Calvin and, later, Ulrich Zwingli, provided their own spin on sola scriptura. Calvin, an unordained lawyer, believed that the Church, led by the scriptures, had an obligation to govern society. Zwingli, further, put this into practice and laid the groundwork for what is often called “the radical Reformation.” And the Radical Reformers are the ancestors for the Baptists and Evangelicals we see today.

Luther tended to believe that the Bible held primacy for the Church and that the Church is obligated to conform to what is written therein. If the Bible is silent on a matter, then the Church has the authority to do what it wants, so long as that action does not contradict something written in the Bible.

The radical Reformers, on the other hand, believed that the Bible held primacy for general society and that people are obligated to conform to what the Bible says—sometimes going so far as to declare the Bible prescriptive in the sense that one must do only what is written in the scriptures; if the Bible is silent on a matter, then that is to be taken as indication that the Bible does not endorse that matter.

The Reformation Era is the context in which Anglican Christianity came of age.

Unlike the rest of Europe, Henry VIII did not seek to reform the Church. Instead, he moved to take the Church in England out from under the political and ecclesial authority of the pope. This put Anglican Christians in a unique situation—as well as subject to a number of conflicts and controversies.

During Henry’s lifetime, the Church in England remained mostly identical with wider Catholic Christianity. It was under his son, the short-lived Edward I, when the European reforms began to affect the Church—under the leadership of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry’s reign. Upon Edward’s death, his sister Mary (the famous “Bloody Mary”) re-aligned the Church in England with Rome and had Thomas Cranmer executed. After her death, her sister Elizabeth I reversed the move to Rome and, with the help of the theologian Richard Hooker (among others), developed what has become known as “The Elizabethan Settlement.”

The Settlement sought to address the changes and challenges of Christianity on England. England was a realm filled with, by this point, Radical Reformers, Lutherans, and Catholic Christians. The work of the Elizabethan Settlement, in addressing these disparate Christian movements, has given us Anglicans a defining term: via media, “The Middle Way.”

Often mistakenly referred to as “the middle way between Catholicism and Protestantism,” The Settlement tends to find a way between Lutheran and Calvinist/Radical Reformation-ism. It gave us what is known as The Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion (found on pages 867-876 of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer). Among those are two Articles that speak directly of the Bible.

The key teaching on Anglican views of the Bible is found in Article VI of the Articles of Religion:

Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation: so that whatsoever is not read therein, nor may be proved thereby, is not to be required of any man, that it should be believed as an article of the Faith, or be thought requisite or necessary to salvation.

This teaching is further reinforced in Article XX:

The Church hath power to decree Rites or Ceremonies, and authority in Controversies of Faith: and yet it is not lawful for the Church to ordain any thing that is contrary to God’s Word written, neither may it so expound one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another. Wherefore, although the Church be a witness and a keeper of Holy Writ, yet, as it ought not to decree any thing against the same, so besides the same ought it not to enforce any thing to be believed for necessity of Salvation.

So, to break this down, Anglican Christianity affirms that the Bible, primarily, contains what is necessary for salvation (this article is titled “Of the Sufficiency of the Holy Scriptures for Salvation”). The context here is that the Church cannot declare something NOT found in the Bible as being necessary for one’s salvation (this addresses a particular Reformation-era controversy surrounding Roman Catholic indulgences). However, if the Church does discern that something extra-biblical is necessary for salvation, then that thing must be “provable”—based in or in harmony with—by the Bible.

Further, the Church’s authority is limited by what is contained in the canon of Scripture. It cannot teach something that is “repugnant” or contrary to what is written in the Bible.

This teaches us that matters of salvation take primacy for us Anglicans in interpreting The Bible. The only “requirements” we have in regards to the Bible are in matters concerning our salvation (which includes the nature of sin, death, the divinity of Jesus, the nature of the sacraments, the bodily resurrection, etc.). We probe the scriptures in search of what saves us, helps us in our salvation life, and how to lead others to experience that salvation. We Anglicans, then, understand the Bible as a cross-oriented book—we read all of it in the shadow of the Cross.

The Bible, for Anglicans, then, is not Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth. It’s not a rule book or life-manual. It contains the story of our salvation. It is a book about Jesus, revolving around Jesus. And we don’t read this sacred book dryly. We enact it, live it, dramatize it. The Book of Common Prayer is 80% scripture (more or less). We put our very lives in its pages, trying to align ourselves with the stories contained therein.

All of this is to say that the reading of the Bible that tends to dominate the discussions of same-sex marriage is a reading we Episcopalians do not endorse.

THE BIBLE AND SAME-SEXUALITY

Please Note: This particular entry will be dealing with explicit statements on human sexuality and sexual practice.

Now that we have addressed how we Episcopalians read the Bible, the next logical step for us is to look at what the Bible itself says on the topic of “homosexuality.”

This will be divided into two sections: The Old Testament and The New Testament. The relevant passages themselves will be posted, followed by commentary.

Before we proceed, I hope you will notice the sparse amount of material here. The Bible doesn’t really say all that much on this topic. As you will see, much of even this is a degree of “reading in” to what is on the page.

What follows is everything the Bible has to say on the matter:

OLD TESTAMENT

The first place to start is with the famous story of “Sodom and Gomorrah.” Indeed, it is from this story that we get the term “sodomy”—which itself has served as the basis for an antiquated term for homosexual males: “sodomites.”

Genesis 19:1-11

The two messengers entered Sodom in the evening. Lot, who was sitting at the gate of Sodom, saw them, got up to greet them, and bowed low. He said, “Come to your servant’s house, spend the night, and wash your feet. Then you can get up early and go on your way.”

But they said, “No, we will spend the night in the town square.” He pleaded earnestly with them, so they went with him and entered his house. He made a big meal for them, even baking unleavened bread, and they ate.

Before they went to bed, the men of the city of Sodom—everyone from the youngest to the oldest—surrounded the house and called to Lot, “Where are the men who arrived tonight? Bring them out to us so that we may have sex with them.”

Lot went out toward the entrance, closed the door behind him, and said, “My brothers, don’t do such an evil thing. I’ve got two daughters who are virgins. Let me bring them out to you, and you may do to them whatever you wish. But don’t do anything to these men because they are now under the protection of my roof.”

They said, “Get out of the way!” And they continued, “Does this immigrant want to judge us? Now we will hurt you more than we will hurt them.” They pushed Lot back and came close to breaking down the door. The men inside reached out and pulled Lot back into the house with them and slammed the door. Then the messengers blinded the men near the entrance of the house, from the youngest to the oldest, so that they groped around trying to find the entrance. (see also Judges 19:16-24 for a nearly identical story)

So here is the classic story that forms the basis of much Christian thinking about homosexuality.

The “sin of Sodom and Gomorrah” is famous even within the pages of The Bible as an example of profound, unspeakable wretchedness committed before God. In the passages prior to this, Abraham (Lot’s uncle) is visited by God and told that the two cities are on the chopping block. Abraham is told that “their sin is very serious” and serves as the basis for their destruction.

But this all raises the key question: what is the sin of Sodom and Gomorrah?

That the men have sex with men (are “homosexual”) is often understood as the wickedness that causes God to burn with rage at the two cities. But what does the Bible itself say?

Our first reference to the sin of Sodom and Gomorrah comes just before the passage we read above: Genesis 18:20 says, “The cries of injustice from Sodom and Gomorrah are countless, and their sin is very serious! I will go down now to examine the cries of injustice that have reached me” (from the Common English Bible).

So, it is “the cries of injustice” that cause God to be angry. What is that injustice?

Later on, Ezekiel the prophet, speaking the Word of God, will say of Sodom and Gomorrah: “This is the sin of your sister Sodom: She and her daughters were proud, had plenty to eat, and enjoyed peace and prosperity; but she didn’t help the poor and the needy. They became haughty and did detestable practices in front of me, and I turned away from them as soon as I saw it” (Ezekiel 16:49-50 NRSV).

The “sin” listed here is failure to help the poor and needy in spite of wealth. They were arrogant (“haughty”). Yes, there’s a mention of “detestable” things that folks could use to fuel the “homosexuality” angle, but we’ll look at that in a moment.

Even Jesus, in the gospels (in a story recorded by Mark, Matthew, and Luke), speaks of the sin of Sodom. But He does so in terms of hospitality, telling the disciples He’s sent out that any city that does not welcome them will face a harsher sentence than what was experienced by Sodom and Gomorrah:

“If anyone refuses to welcome you or listen to your words, shake the dust off your feet as you leave that house or city. I assure you that it will be more bearable for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah on Judgment Day than it will be for that city.” (Matthew 10:14-15 CEB)

And given that Jesus is our final authority in how we read the Bible, we are left with the realization that the sin of Sodom and Gomorrah is not “homosexuality” but inhospitality.

A little context here goes a long way:

Sodom and Gomorrah are first mentioned in Genesis 13, when Lot moves there. Even then they are mentioned as “very evil and sinful against the Lord.”

Next, they are depicted in Genesis 14 as having been conquered and ransacked by a coalition army comprised of soldiers from five kingdoms as part of a civil war. Abraham comes to their assistance to free Lot and winds up helping them achieve victory and a return of their wealth.

So Sodom and Gomorrah are a people who ought to know the importance of assisting people in need. But instead, they use their power to abuse people by raping them as a form of domination (much like is seen in some forms of prison culture today).

What clearly happens in Sodom and Gomorrah is not exemplary of two people of the same sex being in love with each other and desiring a life together before God. This isn’t even categorically “homosexuality.” This is rape. Men raping men rather than expressing peace and hospitality to them.

And that systemic culture of raping foreigners in their midst is the detestable act that God speaks of in the beginning. Which all of us would most certainly understand as profoundly evil.

So this is not a passage about “homosexual orientation” (meaning, a person romantically and physically attracted to a person of the same sex), but about an astounding culture of violence and domination.

We must remember that in the ancient world there didn’t exist Hyatt Hotels or Motel 6. When people travelled they needed to rely on the hospitality of strangers. Travel was already dangerous enough with thieves on the roads. This is why the Torah places an emphasis on welcoming the stranger, saying “remember that you were strangers in Egypt.” God is interested in God’s people creating a trustworthy society where travelers can sojourn without fear of exploitation or abuse.

This underscores the great evil of Sodom and Gomorrah. Here was a people who had experienced the violence of inhospitality themselves and who were given an opportunity to change, but wound up becoming more wicked than before.

Leviticus 18: 19-24

Here we have the go-to passage on homosexuality. This one serves as the clearest example of “the Bible says this is wrong.” I’ve put the passage in a bit of wider context to show how it plays in a larger category of sexual sins in The Torah:

‘Also you shall not approach a woman to uncover her nakedness during her menstrual impurity. You shall not have intercourse with your neighbor’s wife, to be defiled with her. You shall not give any of your offspring to offer them to Molech, nor shall you profane the name of your God; I am the Lord. You shall not lie with a male as one lies with a female; it is an abomination. Also you shall not have intercourse with any animal to be defiled with it, nor shall any woman stand before an animal to mate with it; it is a perversion.

‘Do not defile yourselves by any of these things; for by all these the nations which I am casting out before you have become defiled. (see also Leviticus 20)

How are we to interpret this?

The first issue that any Christian using Leviticus for this discussion has to account for is what St. Paul writes in Ephesians 2: “[Jesus] canceled the detailed rules of the Law so that he could create one new person […]” (Ephesians 2:15). This means, as St. Paul writes elsewhere, that we are “no longer under the Law.” The Law forbids the eating of shellfish, the wearing of mixed fabrics. It also requires that parents stone to death overly disobedient children and that victims of rape marry their assailants.

There are many things in the Law that Christians are quick to say “this no longer applies.” But on issues like homosexuality, they will point at the Law and say, “see?”

But that is a discussion for another time. For the purposes of debate, we will consider what the Law says here.

If we can learn anything from the rabbis it’s that every word of scripture counts.

So, to begin with, this law speaks only to men. Indeed, there is only one verse where lesbian activity is even discussed (see the New Testament section below). Which means that this law is not speaking of “homosexuality” in categorical terms. Rather it is condemning a practice that applies specifically to males—namely, that a man cannot “lie down” with another man as that man would “lie down” with a woman.

The Hebrew word “shakab” means “to lie down” and has a wide range of connotations. It is frequently sexual, but not exclusively—in the Bible it most often refers to sleeping. Context clues us in to the fact that it is sexual (since this prohibition appears in a list of sexual sins). So, a man cannot have sex with another man as he would with a woman. That is the literal reading of this law (so far). Now we have to determine what “as he would with a woman” means. And this is where things get tricky.

For starters, it is impossible for a man to have sex with a man in the way he’d have sex with a woman because men, in general, do not have female genitalia. However, one can easily make the jump to see that, perhaps, the Law is talking about anal sex. A male using the male body as though it were a female’s body. This reads a bit euphemistically, but it seems sound.

This gives us two possible interpretations. The first should be clear: the Bible is forbidding male anal sex. This is the common take-away for many interpreters and the basis for anti-gay views in Christianity (and some parts of Judaism). However, this interpretation doesn’t seem to be as nuanced as the text. Because a woman also has an anus and the law says nothing about forbidding anal sex with a woman. So, it seems that there’s something else going on here. Further, anal sex is not an exclusive practice of male same-sex relationships (contrary to what much popular culture would indicate). So, even if this law is condemning a particular practice, that condemnation does not necessarily apply across the board to “homosexual orientation” and/or practice.

Now, the fact that the law specifies “as with a woman” suggests something emasculating. This is a major concern in the Torah. Indeed, a man who’s been rendered “infertile” is not allowed to come into the Lord’s presence (see Leviticus 21:17ff, Deuteronomy 23:1). The concern seems to be more about a man’s “maleness” than it does with sexual activity. To treat another man as though he was a woman, to emasculate him, is what is considered “abominable” (the Hebrew word which, incidentally, is also used in reference to non-kosher foods in Deuteronomy 14:3).

But there is another aspect to this that deserves further investigation:

In the ancient world it was believed that children came from men. Their semen was seen as a seed (which is why this is the word used in Hebrew) to be planted in the fertile “soil” of the woman’s womb. So the law is very concerned with how semen is used.

As was mentioned above, men were the primary “givers” in procreation, women only serving as the soil for the seed to take root in. Even past the invention of the microscope, people believed that a man’s semen contained a tiny, fully formed human. This speaks also to the Law’s prohibition on bestiality. In a world where people believed in half-human/half-animal beings (like satyrs), the concern was that an animal’s seed might impregnate a woman and create something inhuman.

So this Law is concerned with responsible use of one’s body for the purposes of procreation. We will talk about this further in the next part of this series (on marriage). So, if anything, this seems more in line with a condemnation of abortion than it does homosexuality in that the passage seems to concern itself with what one does with their bodily fluids considered to be very seed of a human life.

This aspect is also partially understood in the Torah’s cleansing rituals. If a man has a nocturnal emission, he is to ritually purify himself. Same if anyone touches blood. Both of these fluids are tied to life, the shedding of life. And the shedding of life always carries with it, in the Torah, a need to for purification.

Ultimately, however, the final verse provides the context we need: “Do not defile yourselves by any of these things; for by all these the nations which I am casting out before you have become defiled.” The giving of children over to Molech, male prostitution, bestiality, these are all examples of idolatrous practices. So the Law is interested here (and elsewhere) in providing the means for Jews to define themselves over and against the idolatrous peoples they are going to encounter and remove from the Promised Land.

Again, the concern here is not categorical “homosexual orientation.” It is, rather, the responsible use of the tools for life and the defining markers of cultural uniqueness.

NEW TESTAMENT

Now that we’ve looked at what the Old Testament has to say on the subject, we turn now to the New Testament.

The first passage for our consideration is another one that is commonly cited by opponents of same-sex marriage:

Romans 1: 25-28 (CEB)

They traded God’s truth for a lie, and they worshipped and served the creation instead of the creator, who is blessed forever. Amen.

That’s why God abandoned them to degrading lust. Their females traded natural sexual relations for unnatural sexual relations. Also, in the same way, the males traded natural sexual relations with females, and burned with lust for each other. Males performed shameful actions with males, and they were paid back with the penalty they deserved for their mistake in their own bodies. Since they didn’t think it was worthwhile to acknowledge God, God abandoned them to a defective mind to do inappropriate things.

There’s a lot here to wade through.

Firstly, this passage is unique in all the Bible because it is the only place where female same-sexual practice is referenced. Secondly, Paul’s arguments hinge on the concepts of a few key words here: “natural,” “traded” (other translations say “exchanged”), and “lust.”

To begin, let’s look at “lust.” Lust is a clearly condemned sinful practice that happens among all sexual orientations. There’s nothing explicitly “homosexual” about lust. That these women and men are acting out of lust is clearly a sinful thing and lust is something that all Christians (whether “progressive” or “conservative”) will agree ought to be condemned.

So here, as we have seen in the Old Testament, what Paul is condemning is not mutual love but lust-based actions. And lust is always going to be selfish and wicked.

Indeed, this lust is of such potency that it causes women and men to make an exchange. They give up sexual desire for the opposite sex and turn it toward their respective sexes.

Many Christians will see this as a prescriptive statement about homosexual orientation, evidence that people “choose” to act according to their forbidden and sexual desires. However, reality does not fit in with this notion.

The experience of LGBTQ people, backed up by psychological science, tells us that they do not “choose” their sexual orientation any more than someone chooses their gender or their race. While the precise “causes” of same-sexuality (as well as bi- and asexuality) is still not known, researches are in agreement that it is something human beings are born into—it is something not of one’s choosing.

At the same time, this fact does not diminish Saint Paul’s condemnations. Because while he might not be condemning “homosexuality” as we understand it today, he is clearly still condemning a perversion. Because he is speaking of people making a choice to perform certain acts with their bodies, choices rooted in lust rather than love.

Following this, Saint Paul is clearly claiming that what these women and men are doing is “unnatural.” But what exactly does Paul understand “natural” to mean?

This is particularly tricky because “nature” has been (and remains) a fluid concept. For many in the Ancient World, “nature” referred to something ordered. Today, we tend to view “nature” as being something wild, un-contained, somewhat disordered (or having its own order over and against human concepts of order which are often seen as means of containing and controlling).

Paul uses “nature” to describe something a couple of key places in his writing. In I Corinthians, he writes: “Does not nature itself teach you that if a man wears long hair, it is degrading to him?” (I Corinthians 11:14a NRSV).

This reveals to us the differences between how we understand “nature” and how Paul understood it. Because, for us, long hair is “natural”—meaning, hair naturally grows, therefore long hair can only happen by virtue of hair doing what comes naturally. So, Paul’s concept of “natural” is an iffy concept for us today.

But Paul speaks of “nature” in another place in Romans: “If you [Gentiles] have been cut from what is by nature a wild olive tree and grafted, contrary to nature, into a cultivated olive tree, how much more will these natural branches be grafted back into their own olive tree” (Romans 11:24 NRSV).

So Saint Paul acknowledges that God does something “unnatural,” something “contrary to nature,” in bringing the Gentiles into the Promises of salvation.

And all of this really helps drive home Saint Paul’s larger point in Romans 1 and 2. You see, we’ve gotten far too caught up in the particulars of what Paul writes here that we’ve lost the big picture of what he’s trying to do. He’s not actually interested in condemning particular sins or people—indeed, Paul is quite wary of risking the creation of a new Law so much so that he often avoids precise language in instances where he does condemn particular behaviors.

Paul is, instead, building a crescendo in order to hit an arrogant church with a dose of humility.

Saint Paul is writing to a church made up of a mix of Jewish and Gentile Christians, at a time when Gentiles were relegated to second-class status in The Church. He opens his letter playing to the Jewish Christian elitism (and maybe even a degree of general Christian elitism shared by both Jews and Gentiles in The Church). The description we get in Romans 1:18-32 is something that clearly describes the Roman and Greek pagan aristocracy. He is hitting a number of Jewish beliefs about idolatry: that it willfully ignores the revelation of God of Israel and is the result of self-imposed spiritual blindness, even somewhat mocking the Greek philosophers (“claiming to be wise they became as fools”). In Jewish thought, idolatry is conceived of in terms of adultery and sexual immorality (largely due to the fact that many ancient religious practices involved temple prostitution) and that the worship of idols will lead people to debased sexual practices (this is indicated by the life of Solomon in I Kings 11, who turns to idols due to his love of “foreign women”).

So one can easily read this passage as Paul whipping his crowd up. It is important to keep in mind that Paul’s letters were meant to be listened to, not read on a page. They were written for his assistants to read to the churches, performed somewhat like a sermon.

Here’s Paul saying, essentially, “you all know how wicked those pagans are; how ugly and twisted their practices are.” And Paul’s audience is nodding along. They’re thinking “alright alright, Paul’s really giving it to those disgusting pagans! I like this guy!”

And this builds and builds and builds… until Paul drops a bomb in Romans 2:1—“So every single one of you who judge others is without any excuse. You condemn yourself when you judge another person because the one who is judging is doing the same things.”

So Paul’s using biases and generalizations to drive home a particular point: all have sinned and fallen short of God’s glory (Romans 3:23). And God has demonstrated an enormous and scandalous grace in doing something contrary to nature by bringing in the Gentiles, a people seen as unclean and detestable by “the faithful.”

So these first two chapters of Romans aren’t exactly about condemning same-sex love. They’re about reminding a self-righteous Church that they are as dependent on God’s grace as “those people” that they want to condemn.

Now the next two passages will be discussed in tandem, because the issues in them are something they have in common:

1 Corinthians 6:9-11 (NASB)

Or do you not know that the unrighteous will not inherit the kingdom of God? Do not be deceived; neither fornicators, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor effeminate, nor homosexuals, nor thieves, nor the covetous, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor swindlers, will inherit the kingdom of God. Such were some of you; but you were washed, but you were sanctified, but you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and in the Spirit of our God.

1 Timothy 1:8-10 (ESV)

Now we know that the law is good, if one uses it lawfully, understanding this, that the law is not laid down for the just but for the lawless and disobedient, for the ungodly and sinners, for the unholy and profane, for those who strike their fathers and mothers, for murderers, the sexually immoral, men who practice homosexuality, enslavers, liars, perjurers, and whatever else is contrary to sound doctrine.

Looking at these passages it seems things could not be any more clear. After all, the word “homosexual” shows up. It is obvious that the Bible condemns this as sin.

The things to look at here have to deal with translation, particularly the words “effeminate” and “homosexual.”

“Effeminate” is the English translation of the Greek word malakia which means “soft.” Interestingly, this word is sometimes omitted in English translations of the Bible, seemingly subsumed into the phrase “both participants in same-sex intercourse” (as in the otherwise excellent Common English Bible translation).

Bishop Gene Robinson has argued that it refers to people being morally weak. The antonym of this word in Greek is karteria, which means “patient endurance.” So, rather than saying that someone who is “effeminate” will not enter into the Kingdom of God, it appears that Paul is referring to someone who is “soft-willed” rather than “enduring with patience.” To put this in concert with one of Jesus’ parables, this would be the seed that falls on rocky ground (see Matthew 13:20-21).

In regards to “homosexual,” many translations, use this word to translate the Greek word arsenokoites,which is the combination of “men” and “bed” (arsen referring to “male” or “man” and koites meaning “bed”—it’s where we get the word “coitus” used in English).

The first edition of the New International Version of the Bible (in 1973) was the first English translation to translate arsenokoites as “homosexual.” Prior translations, like the King James Bible, used phrases like “abusers of themselves with mankind” (in 1 Corinthians 6:9) and “them that defile themselves with mankind” (1 Timothy 1:10).

The problem with using the word “homosexual” to translate this term has to do with the fact that, like with what is read in Leviticus, arsenokoites, in its literal sense, refers specifically to males (whereas “homosexuality” is a gender-neutral term). Secondly, “homosexual” was a word that was invented (in German) in the late 1800s for use in a psychological dictionary when homosexuality was considered a mental disorder. So “homosexual” is already a loaded word referring to something that is likely quite different from what Saint Paul is talking about.

The other major problem with using “homosexual” here is that, from what we can gather, arsenokoites is a word Saint Paul invented. It shows up nowhere else other than the Greek New Testament (and, of course, ancient Greek Christian commentators quoting it). What, precisely, Paul was referring to here is lost to us. (It has since been pointed out to me that “arsenokoites” is a kind of combination word that uses the Greek terms from Leviticus 18 in the Greek translation of the Old Testament—the version of the Old Testament Saint Paul would have known and read. I’m adding this note here in order to be transparent. I’ve not done a lot of theological or scholarly reflection on this since learning about it, to be honest. —ed.)

One can easily make the case that it refers to male sex slavery/prostitution. Koites can also refer to a bed-chamber, suggesting perhaps one being a “kept man.” So the case could be made that Paul is condemning a practice of engaging in abusive and exploitative male same-sex relationships.

But we don’t actually know for sure.

***

Now that we’ve looked at all the Bible has to say on the matter, I want to reiterate a couple of key points:

—The Bible only ever explicitly condemns sexual acts between males (lesbian activity only really alluded to).

—What the Bible does condemn turns out to be somewhat vague, or at least not what we’ve popularly interpreted/translated it to mean.

—The term “homosexual” is a bad term to translate a vague Greek word.

—What the Bible condemns is something that does not look like mutually-shared, mutually offered same-sex relationships.

This last point is crucial. The Bible is clearly condemning something, and something wicked. What precisely that condemned thing is, is not completely clear.

Or is it?

How are we to know?

Jesus tells us that the Law is summed up in this statement: Love God with all your heart, mind, and soul and love your neighbor as yourself.

Elsewhere we are told that love is defined this way: Jesus gave Himself for us. (Romans 5:8; I John 4:10-16)

So this means that the Law, as Christians are to understand it, is to be read through a lens of love—a love defined by the actions of Jesus Christ.

This goes back to what we discussed in the beginning: Anglican Christians read the Bible primarily through Jesus, understanding scripture to be about our salvation more than anything else.

The former rector of The Chapel of Saint Andrew, The Rev. Steve Zimmerman, in his own essay on human sexuality in The Church (entitled Authority and Sex in the Church and written in 2000) writes of Anglican understandings of the Bible:

“[Martin Luther] expressed his view of scripture by saying, ‘The Bible is the manger, in which the Christ child is laid, in which there is also, much straw’ […] The Anglican view of the character of the Bible’s authority also comes closer to Luther’s, than to Calvin’s and the Reformed tradition [in that Anglicans] agreed with Luther that the Bible’s authority lies in its witness. Anglicans, however, emphasize scripture’s witness to Christ, not just to the gospel of justification by faith. Scripture bears witness therefore to a person, Jesus Christ, the living Lord, not a message.”

So what this means for us is that the conversation is primarily about this question: does the love of two men or two women look like the love Jesus Christ embodies?

In light of that, we can hold those kinds of same-sex relationships up to what is written in the Bible, in the passages above, and can clearly see that those relationships—rooted in Christ-like love—are not reflected there. Indeed, those kinds of same-sex relationships help further reveal the kinds of evil being condemned in scripture.

We’re not talking about relationships based on lust or exploitation or violence. We’re talking about relationships based on the mutual offering and receiving of love, in like manner to Jesus Christ. And now the question becomes: are those relationships compatible with Christian views on marriage?

AND IN THE END...

(NOTE: The third and fourth parts of the series looked at the history of marriage and then got into the weeds on the actual marriage canon itself. I’m not including that in this because it doesn’t seem as relevant to the current discussion. But if you disagree, let me know on Mastodon and I’ll happily post those! —ed.)

To conclude this series I felt it was helpful to offer my own personal thoughts on the matter (at least more so than I have throughout this series).

One of my friends, after the House of Deputies vote made the new resolution on marriage official, said “alright, now we need to teach this.” What he meant by that was that The Episcopal Church reaffirmed marriage (which itself is amazing and praiseworthy—we could have caved to the wider culture and made marriage completely arbitrary, but instead we reasserted it). Because we reaffirmed marriage, we need to start talking to people about why they get married.

This means saying that, as a Church, we believe that sexuality is reserved for the marriage relationship.

We can no longer just sort of turn a blind eye and act like anything goes. If we’re going to reaffirm and expand marriage, then that means we need to start having difficult conversations about the relationships among the people in our congregations.

Now, here’s the part where I’m going to come across as contradictory from what I just said above:

I think that we’ve largely gone about this the wrong way from the get-go. The same-sex marriage conversation, in The Church, has never been adequate. Indeed even the words of Immorten Joe (from Mad Max: Fury Road) come to mind: mediocre.

This is because we got caught up in sexuality.

In perhaps the most basic terms possible, the same-sex marriage discussion has really been about whether or not it’s okay that people act on the stirrings in their genitals.

Growing up in a fundamentalist Southern Baptist environment and then becoming an Anglican Christian in college (while attending an evangelical university), I’ve talked far too much about sex.

As a teenager the question was always some degree of “how far is too far?” Then it became “when is it really sex?” After which it was “is sex like being married to someone?” And finally “if I love them I can have sex with them, right? The intention was marriage so…”

Every person of my age and background has had these conversations. We went to youth camps where they were discussed. We were force-fed books that talked about this.

It was all, really, “I want to have sex, but I want to have sex correctly in the eyes of God.”

The way we’ve approached same-sexuality in the Church is no different from this. We’ve been asking, for thirty years or so—regardless of sexual orientation—“is the sex people want to have okay with God?”

And, so, for that entire time the Church has been obsessed with sex. Ironically we criticized TV shows for focusing too much on sex while never once acknowledging that we talked about it just as much and with as much focus.

Sexuality is a psychological term, the product of the 20th century. Perhaps the most famous writers on the subject are Freud, Kinsey, and Foucault. It is defined nowadays, more or less, as the brain-chemical process one experiences when they look at or interact with another person.

This notion of “sexuality” gave us the psychological concepts of “attraction” and “orientation.” Some people are attracted to members of a different sex (or, more archaically, “gender”), while others are attracted to members of the same sex. Still others found that they were attracted to both.

That attraction was defined under the umbrella term of “sexual orientation.” People attracted to members of the same sex or gender are homosexually oriented. The same logic follows for heterosexual orientation and bisexual orientation.

The problem with all of this is that human beings are in danger of being reduced to a process of brain chemistry. That the kind of person that I am is largely defined by what my brain does when I’m around a particular human being.

The result of all this talk of orientation and attraction is that it permitted a couple of key phenomena:

Firstly, one could distinguish between orientation and action. This is expressed in the Catholic Church’s teachings on same-sexuality, that acting upon one’s orientation is the sin but the orientation itself is not sinful.

Secondly, and following the above bifurcation, a focus on brain-chemistry-as-personhood-definer does not provide a satisfactory case for the acceptance of same-sex persons for the Church. Because one could easily argue (and have argued) that orientation might be the process of a chemical imbalance. Therefore, one’s sexual orientation might be akin to a handicap or a disease that needs to be cured or corrected. And from here we find ourselves in a circular argument destined to go no where.

Instead, how the Church ought to be talking about this is in terms of love. Case in point: David and Jonathan.

In the Bible is a story of same-sex love. Whether or not it was romantic or platonic is still a matter of (significant) debate. What is not up for grabs here is whether or not the story reflects two men sharing love for each other. This latter notion is made explicitly clear throughout the story, where we are told no less than four times over a number of chapters and in two books, that David and Jonathan share love for each other.

Many Christians get uncomfortable with this story because it’s been made a matter of sexual orientation. In short, we don’t know the sexual orientation of either David or Jonathan. All we know is what the story tells us. We can speculate, sure (which is what makes studying the Bible fun), but we can only walk away with what the story says.

And the story gives us love. And not only that, but the Bible endorses this story of love implicitly—by including it in the canon of scripture.

So the question for us Christians becomes: can we bless love between two men or two women?

And this is a much more honest field for discussion and thought and prayer. Because sex is a very small part of marriage. Sex and sexuality are only a small part of what makes us who we are, as people.

Are there Christian teachings and views on sex? Sure. But that’s not what is being asked when a couple comes to the Church seeking a blessing on their marriage. What IS being asked is a blessing on their love for each other and the life they want to share with each other.

If marriage was a matter of blessing sex, then every pre-marital counseling series needs to include an investigation into what kind of sex a couple is interested in and then it needs to be held up to what the Bible teaches. To be blunt, these conversations would need to address things like: Can BDSM be part of a Christian marriage? What about role-playing (is it effectively adultery since you’re pretending to be someone else)? Toys? Can one use toys? Any positions that might be problematic?

Is there a place for this? Yes. It’s for married couples to discern and pray and discuss. Because it is in marriage, for Christians, that sexuality finds its fullness. But Christian marriage is not simply a blessing of one’s sexuality. It is the blessing of a relationship. It is a celebration of love, putting that love in concert with the love expressed by Jesus toward the Church—incidentally, described as a wedding at the end of the book of Revelation, one that ostensibly involves multiple people of all genders marrying Jesus.

So, again, the question remains: can we, ought we, bless love between two men or two women?

Because we have canonized the story of David and Jonathan we’ve already given a resounding YES to this question.

Love utterly changes the conversation.

When we approach this topic through a lens of love, we begin to see a redefinition of our old interpretations of things. The old proof-texts get a new gloss. Leviticus 18, Romans 1, etc. maintain their traditional integrity because what they reflect is not love—and is, thus, truly sinful. Comparing their contents to the example of faithful same-sex love—David and Jonathan love—reveals their intent. The Bible will always condemn lust, abuse, perversion.

But Scripture always affirms love.

As one of the wedding readings for Episcopal Marriage liturgies says: “I am now taking this kinswoman of mine, not because of lust, but with sincerity” (Tobit 8:7).

We’ve always condemned blessing lust. We’ve never blessed lust. We recognize that lust has no part in Christian marriage or morals. Love reveals the evils of lust.

Leviticus 18, Romans 1, these are not speaking of David and Jonathan. They are speaking of lust. Of perversion.

No one is asking the Church to bless what’s discussed in Leviticus 18 or any of the other proof-texts. Instead, we are asked to bless love.

And so our task, as the Church, is to affirm what is already affirmed in Holy Scripture: love can be found between two people of the same sex. And that love is honorable and to be remembered and celebrated.

What’s cool, to me, in this, is that scripture is always true.

We aren’t required to do any crazy interpretive gymnastics with the Bible. What the Bible says remains true. What is condemned by Paul in Romans, I Corinthians, I Timothy remains condemned—we don’t say “well, Paul was wrong here and we now know better.” No, instead we get to better understand what it is that Paul is condemning.

When this is about love we can hold things up to the Bible and see what the Bible is saying. And we then get to affirm something new and profound while letting the Bible speak its truth evermore!

When two people come to the Church with their love, we bless it. We bless it and send them on their journey—supporting them with our prayers and the hope that God is working transformative things in their lives together.

It was never supposed to be about just sex.

It’s always been about love.

#Christianity #Jesus #Episcopal #Anglican #Marriage #LGBTQ #SSM #Bible #SameSexMarriage #Equality

The Rev. Charles Browning II is the rector of Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church in Honolulu, Hawai’i. He is a husband, father, surfer, and frequent over-thinker. Follow him on Mastodon and Pixelfed.

Though this might have more to do with me being a weeb...

Though this might have more to do with me being a weeb...

Proof!

Proof! This movie is preposterous and amazing at the same time

This movie is preposterous and amazing at the same time These things

These things not even the one where Godzilla fights a Monsanto creation

not even the one where Godzilla fights a Monsanto creation I think I just wrote my Good Friday sermon.

I think I just wrote my Good Friday sermon. *Sup?*

*Sup?*

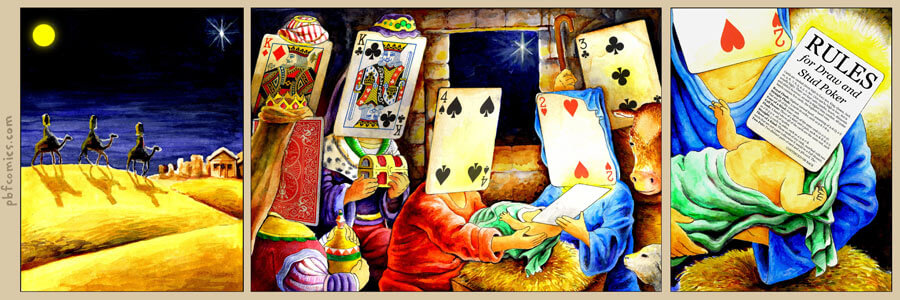

Honestly, this image is probably the actual best representation of what “the Logos made his home among us” means. (

Honestly, this image is probably the actual best representation of what “the Logos made his home among us” means. (